Recently, the New York Times Magazine has been a hotbed for articles covering business in or affecting developing countries. Last week I wrote about a potentially more unconventional way of looking at the counterfeit goods trade from the perspective of major apparel companies. More recently, an incredibly impressive article was written by Andrew Rice, on a simple foodstuff called Plumpy’nut.

Recently, the New York Times Magazine has been a hotbed for articles covering business in or affecting developing countries. Last week I wrote about a potentially more unconventional way of looking at the counterfeit goods trade from the perspective of major apparel companies. More recently, an incredibly impressive article was written by Andrew Rice, on a simple foodstuff called Plumpy’nut.

Seriously this article covers it all; patent issues, lawsuits, lobbying groups, problems with foreign aid, agricultural and a variety of approaches to malnutrition and poverty.

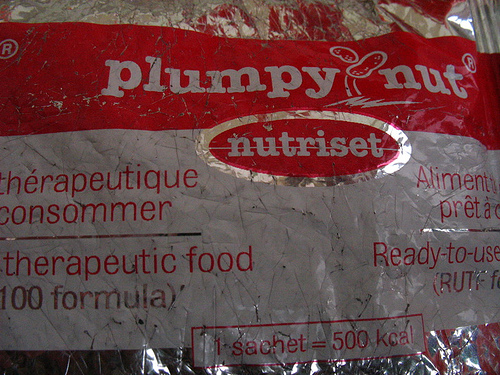

Plumpy’nut is a peanut butter type substance that is packed with various nutrients and does not require refrigeration and does not spoil easily. It has been said to aid a severely malnourished child in less that two months and can be manufactured easily, which would allow for developing countries, particularly those in Sub-Saharan Africa to make it themselves, thus providing a potentially sustainable business model.

There’s only one problem, the product, which was developed by a Frenchman, André Briend and made by a private French company called Nutriset, holds and attempts to enforce an extremely strict patent. From a business perspective, one can understand why. The market currently stands at $200 million and there are an estimated 20 million malnourished worldwide. Here’s where the moral/ethical argument of the role of business and development comes to a head. The company is arguing that they are remaining diligent about the patent in the developed world, but plan to franchise the product out to developing countries in the coming years. A factory has been built in Tanzania.

While it’s easy to demonize Nutriset for this behavior – after all, competition should be good for the consumer – there is evidence of some current lawsuits and patent challenges possibly being backed by big western corporations and the peanut lobby. Sadly, while competition is generally positive, one of these larger, possibly less responsible corporations could simply take over the industry the same way they claim Nutriset is. If you don’t think lobbying and corporate interests in the US have a major influence on the state of developing countries please look again (cotton is a good place to start).

This is how the original debate is framed, but I credit Rice for digging deeper and really looking at the underlying issues here. One is the trouble with the aid-based model. “In 2005, it [Doctors Without Borders] distributed Plumpy’nut to 60,000 children with severe acute malnutrition during a famine in Niger. Ninety percent completely recovered, and only 3 percent died. Within two years, the United Nations endorsed home care with Plumpy’nut as the preferred treatment for severe acute malnutrition. Nonetheless, Schultink [chief of nutrition UNICEF] estimates that the product reaches only 10 to 15 percent of those who need it, because of logistical and budgetary constraints.” Clearly a great product and clearly a problematic delivery method.

Of course this type of problem is not limited to Plumpy’nut nor is Plumpy’nut the “silver bullet” that the UN and others in the global health world would like it to be. It’d be nice if all franchises and other business opportunities were sustainable, but that’s not always going to be the case. It’s a wonderful product and should play a significant role in humanitarian assistance and perhaps post conflict efforts, but as Rice and many others including recipients on the ground have pointed out, products/projects like these do not promote sustainable development or promote independence from the West. Nutriset must follow through and allow citizens of developing countries to produce and sell this product for their benefit because as the article wraps up, a Haitian women stated that there was “no hope for other serious problems she faced, like the fact that she had no job and the tin roof over her shack leaked.” Perhaps, if or when she becomes part of the Plumpy’nut business such issues will be ameliorated.

Image Credit by emily b sneaky via Flickr under a CC license